We explain what Epicureanism is, its origin and why it focuses on pleasure. In addition, we tell you how it influenced modern philosophy.

What is Epicureanism?

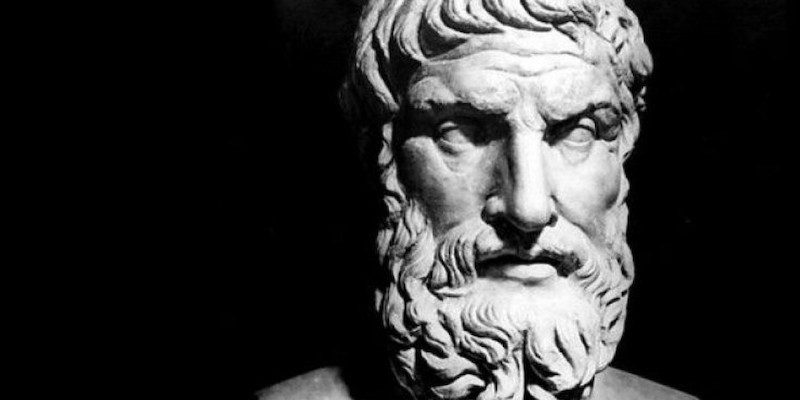

Epicureanism It is a philosophical movement whose maximum objective is to seek modest and lasting pleasure. Founded by Epicurus of Samos (341-270 BC) on the outskirts of Athens, Epicureanism is often confused with mere hedonism (a philosophical doctrine that identifies pleasure with the good). This is due to the fact that Epicurus and his followers, the Epicureans, propagated a philosophy based on the pursuit of pleasure.

Although it is true that Epicurus, like Aristippus (435-350 BC), was a hedonist, his doctrine should not be reduced to banal and selfish pleasure. The pleasure pursued by epicureans is modest and sustainable over time, whose form is that of ataraxia (tranquility and freedom from fear) and aponia (absence of bodily pain).

The Epicurean school had an important development in ancient Greece, whether in its opposition to Platonism or its later rivalry with Stoicism. Its greatest development occurred in the late stage of Hellenism and during the Roman era.

Both Lucretius and other Roman philosophers compiled and unified Epicurean teachings until their near disappearance in the 3rd AD. C. Several centuries later, the Epicurean current reappeared in the Enlightenment and remained in vogue even until contemporary times.

History, origin and etymology of the term “epicureism”

The Epicurean school was founded in Athens around 306 BC. C., year in which its founder, Epicurus, established himself in the city. It is from him that the Epicureans, his followers, take their name. That this current is called Epicureanism indicates, due to the suffix “-ism”, that it is a philosophical doctrine. His followers are also known as “the garden philosophers.”

Epicurus founded his school on the outskirts of Athens, on the road to the port of Piraeus. It was known publicly as Jardín, or kêpos in classical Greek (κῆπος). The Garden was made up of men and women, which was a novelty at the time. There, a simple way of life was promulgated, isolated from political and social life, and which encouraged above all the practice of friendship.

The Garden was actually a large rural space, foreign to the city, whose practical and hidden life challenged the ideas and teachings of the Platonic Academy and even the Aristotelian Lyceum, both schools with which it coexisted. At its doors, according to Seneca in his Epistolaemorales ad Luciliumthe following was inscribed: “Stranger, your time will be pleasant here. In this place the greatest good is pleasure.”

The school opened its doors to people of all types, whether free men, women or slaves. Internally, it was organized according to a strict hierarchy, whose main positions or strata are the following:

- The philosophers or philosophoi.

- The schoolchildren or philologoi.

- The teachers or kathegetai.

- The imitators or synetheis.

- Students “in preparation” or kataskeuazomenoi.

Main idea of Epicureanism: pleasure

Epicurus promulgated above all things a constant search for pleasure. Only through pleasure could the healing of the human soul be achieved. A happy and pleasant life could overcome the barriers of physical pain or spiritual discomfort. Thus, philosophy had to serve to make man happy: “philosophy is an activity that with words and reasoning seeks a happy life” (fragment 219 as compiled by Esteban Bieda in Epicurus).

- However, The search for pleasure should not be understood as an abandonment of reason for a life dedicated to leisure. It is about directing intellectual activity to obtain pleasure and tranquility. It does not matter if in this search the teachings of ancient masters must be set aside. It could even be the case that they would have to be corrected.

- The important thing for Epicureanism was to be able to reach the state of ataraxia and that is why, in one of his surviving fragments, Epicurus says: “Flee from all education, happy man, unfolding the sails of your boat” (fragment 16 as compiled by Esteban Bieda in Epicurus).

- In short, the pleasure sought was more inclined to a mental pleasure than a physical one. Unnecessary desires had to be suppressed, such as the lust for power, the desire for fame or those that could arise during political life.

- On the other hand, those fears considered to be the main causes of conflict in life should be eliminated. According to Epicurus, these were the fear of the gods (punishment) and death (end).

Epicurus considers that this abandonment of the previous and previous philosophical content occurs because it was nested in a sterile intellectualism and could not account for the path to man’s happiness. Fragment 221 in Epicurus says:

«Empty is the word of that philosopher by action of which no affliction of man is cured. For just as there is no benefit of medicine if it does not expel diseases from the bodies, in the same way it happens with philosophy if it does not expel the affection of the soul.

Pleasures according to Epicureanism

Pleasures, according to Epicureanism, can be differentiated into two broad categories:

- Pleasures of the body. They are those that involve pleasant sensations or freedom from pain. They only exist in the present.

- Pleasures of the soul. They are those that require a process and mental state, such as the feeling of joy (khara), ataraxia and aponia.

These pleasures, and also suffering, as their opposite, are linked to the satisfaction of appetites. The appetites according to Epicureanism can be:

- Natural and necessary appetites (eat, shelter, sleep)

- Natural and non-necessary appetites (sexual enjoyment)

- Unnatural or necessary appetites (fame, money, power)

The search and completeness of pleasure as a supreme good depend on the satisfaction of the appetites divided into these three large groups, and their subsequent balance.

Types of knowledge according to Epicureanism

Epicureanism can be divided into a physical, a canonical and an ethical one.

- The physics He was dedicated to the study of nature from an atomistic perspective.

- The canonical or criterialogy, dealt with the criteria by which we can differentiate the false from the true.

- The ethics It was that branch of Epicurean thought that developed an ethical hedonism, and in whose work could be seen the culmination of the entire system of Epicurean philosophical thought.

Influence of Epicureanism on modern philosophers

Epicureanism has reached the most diverse and different corners of the philosophical world. Thus, a list of different philosophers and thinkers includes those who have collected and claimed part of the Epicurean teachings. Among them we have the following:

- Walter Charleton

- Robert Boyle

- Francisco de Quevedo

- John Locke

- Immanuel Kant

- John Stuart Mill

- Karl Marx

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- Michael Onfray

What does it mean to be an epicurean today?

An epicurean person is considered one who practice moderate, honest and wise love or enjoyment. An Epicurean knows the different arts of life, sexual enjoyment in its moderation, the state of calm or ataraxia and even forms of amonia as the absence of pain and a sign of happiness.

However, it is common to misuse the term, especially when a person of Epicurean practices is confused with one who practices hedonism and the search for fleeting pleasures, such as excesses of the body and mind.

Documents of Epicureanism

We owe Diogenes Laertius (3rd century BC), Greek historian, the titles of at least forty of Epicurus’ works. As has happened with most ancient texts, Epicurus’ teachings survive only in quotations and fragments collected by later philosophers.

Thus, today, we have three letters (to Herodotus, Pythocles and Menoeceus), a series of capital maxims, some fragments that appear in the Vatican codex Gnomologium Vaticanum and works of his disciples, such as Philodemus of Gadara or , later, Sextus Empírico, Plutarch, Cicero and Seneca, among others.

Continue with: Metaphysics

References

- EpicurusEsteban Bieda, The philosophical revolt.

- WorksEpicurus, Altaya.

- EpicurusCarlos García Gual, Alianza Editorial.

- Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epicurus/

- Texts in Greek at http://www.hs-augsburg.de/~harsch/graeca/Chronologia/S_ante03/Epikur/epi_intr.html