There are certain phrases that get repeated so often they almost lose their meaning. “Knowledge is power” is one of those sayings people throw around without really thinking about where it came from or what it actually implies. But here’s the interesting part: this simple phrase has sparked centuries of philosophical debate about how information, education, and authority intersect in human society. The relationship between knowing things and wielding influence turns out to be way more complex than a motivational poster slogan suggests. And the phrase itself? Well, its origins involve a case of mistaken attribution that lasted for centuries.

What Does ‘Knowledge is Power’ Actually Mean?

Most people hear this phrase and think it’s pretty straightforward. Learn more stuff, get more power. Simple, right? But the meaning has layers that get overlooked when it’s reduced to a bumper sticker.

The phrase is commonly attributed to Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626), the English philosopher and statesman who helped shape early modern scientific thinking. People credit him with the Latin version Scientia potentia est. Except that’s not quite accurate. What Bacon actually wrote in his Meditationes Sacrae (1597) was ipsa scientia potestas est, which translates more like “knowledge itself is power.” Close, but not identical.

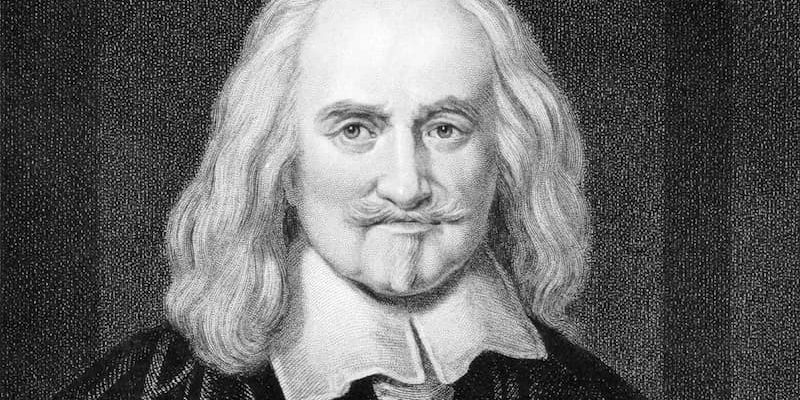

Here’s where it gets interesting. The exact phrasing “knowledge is power” first appeared in English in the 1668 edition of Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679). Hobbes had worked as Bacon’s secretary in his younger years, so there’s definitely a connection. But the phrase we use today came from Hobbes, not Bacon.

Why does any of this matter? Because understanding the phrase’s origins helps clarify what it means. Bacon was focused on scientific knowledge—the empirical understanding of natural phenomena. His point was that understanding how nature works gives humans the ability to manipulate it, to achieve practical ends. Knowledge wasn’t just contemplative; it was active, useful, transformative.

Hobbes took this idea further. For him, knowledge meant power in a more political sense. Understanding how societies function, how people behave, how institutions operate—that knowledge gives you the ability to influence, control, and organize human affairs. It’s not just about mastering nature; it’s about mastering social reality.

Today, the phrase gets interpreted in various ways. The most common understanding is educational: accumulating knowledge through learning increases your possibilities for success, influence, and social mobility. Go to school, learn skills, gain expertise—and you’ll have more options, better opportunities, greater ability to shape your circumstances. This interpretation underlies modern education systems and meritocratic ideals.

But there’s a darker interpretation too. Knowledge is power can mean that those who control information control society. Gatekeepers of knowledge—whether religious institutions, universities, corporations, or governments—wield power by deciding who gets access to what information. In this reading, the phrase isn’t aspirational advice; it’s a description of how power structures actually function.

The Relationship Between Knowledge and Power

So how exactly does knowledge translate into power? The connection isn’t automatic or simple. Different kinds of knowledge create different kinds of power.

Technical knowledge gives you the ability to do things others can’t. Know how to code? You can build software. Understand engineering? You can design structures. Master surgery? You can save lives. This is probably the most obvious type of knowledge-power relationship. The person with expertise can accomplish tasks that remain impossible for those without that expertise.

This creates dependency. If you don’t know how to fix your car, you depend on mechanics. If you don’t understand tax law, you need accountants. Specialized knowledge creates professional classes whose power derives from their exclusive understanding of complex domains. This is why professional associations, licensing requirements, and educational credentials exist—they formalize and protect these knowledge-based power structures.

Strategic knowledge works differently. This isn’t about technical skills but about understanding situations, reading people, anticipating consequences. Think of a chess master who doesn’t just know the rules but understands patterns, strategies, psychological dynamics. This type of knowledge lets you navigate complex social and political environments effectively.

Leaders need this kind of knowledge. So do successful business people, diplomats, lawyers, really anyone operating in competitive environments where understanding hidden dynamics matters. The person who knows what others want, what they fear, what motivates them—that person has power regardless of their formal position.

Cultural knowledge represents another dimension. Understanding the norms, symbols, references, and unwritten rules of a culture or subculture gives you insider status. You know what to say, how to dress, which behaviors signal membership. This knowledge grants social power—acceptance, trust, opportunities available only to those “in the know.”

Think about how this plays out. New immigrants often struggle not because they lack skills but because they don’t understand the cultural codes of their new society. Meanwhile, people born into privileged social circles inherit cultural knowledge that opens doors throughout their lives. It’s invisible but powerful.

Information as commodity makes the knowledge-power link explicit. In markets, information creates advantages. Knowing what competitors don’t know, what regulators will do, what trends are emerging—this information has direct monetary value. That’s why insider trading is illegal; it’s too obviously unfair when knowledge translates directly into wealth.

More broadly, whoever controls information flow controls narratives, shapes perceptions, influences decisions. Media companies wield power this way. So do governments deciding what information to classify or release. In the digital age, tech companies controlling algorithms that determine what information people see have become some of the most powerful entities on Earth.

Francis Bacon and the Birth of Modern Science

Understanding Bacon’s contribution requires context. He lived during a period of massive intellectual transformation—the early modern period when medieval ways of thinking were giving way to new approaches.

Bacon wasn’t primarily a scientist in the experimental sense. He was a philosopher, lawyer, and politician (he served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England). But his philosophical work laid crucial groundwork for the scientific revolution that would follow.

His big idea? That knowledge should be pursued through observation and experimentation rather than deduction from ancient authorities. Medieval scholars had treated Aristotle’s writings as basically infallible. If you wanted to understand nature, you studied what Aristotle said about it. Bacon said: No. Go look at nature itself. Observe, experiment, test your ideas against reality.

This empirical approach became foundational for modern science. Bacon outlined what would become the scientific method—systematic observation, hypothesis formation, experimental testing, refinement of theories based on evidence. Revolutionary stuff for his time.

When Bacon wrote about knowledge being power, he meant it practically. Understanding natural laws gives humans the ability to harness nature for human benefit. If you understand mechanics, you can build machines. If you understand chemistry, you can create new materials. Knowledge isn’t just contemplative wisdom; it’s the key to technological mastery.

Bacon envisioned science as a collective, progressive enterprise. Scientists would build on each other’s work, gradually expanding human knowledge and capabilities. He imagined scientific institutions where researchers would collaborate systematically. (The Royal Society, founded a few decades after his death, embodied this vision.)

There’s irony here though. While Bacon championed empirical investigation, he wasn’t particularly good at actually doing it himself. His experimental work was limited and sometimes sloppy. His genius lay in articulating the philosophical framework that others would successfully implement. He saw where science should go, even if he didn’t personally get there.

Thomas Hobbes and Political Power

Hobbes took Bacon’s ideas about knowledge and power in a more political direction. Where Bacon focused on mastering nature, Hobbes was concerned with mastering society—understanding human nature well enough to design stable political systems.

His masterwork Leviathan (1651) appeared during and after the English Civil War, a period of devastating political chaos. Hobbes had witnessed how quickly social order could collapse into violence. His central question: How can humans create stable societies that don’t tear themselves apart?

His answer involved understanding human nature scientifically. Hobbes believed humans are fundamentally self-interested and competitive. In the “state of nature” without government, life would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (that’s another famous Hobbes phrase). People would be in constant conflict.

To escape this condition, humans need to understand political mechanics well enough to design effective governments. Knowledge of human nature, social dynamics, and institutional design becomes the foundation for political power and social stability.

In his earlier work De Corpore (1655), Hobbes explicitly stated that the purpose of knowledge is power, and the goal of speculation is the ability to trigger action or produce change. Knowledge isn’t valuable for its own sake; it’s valuable because it enables us to do things, to achieve outcomes, to exert our will on the world.

This is pretty different from ancient and medieval views that treated contemplative wisdom as the highest form of knowledge. Hobbes was thoroughly modern in his instrumentalist view. Knowledge matters because of what it lets you accomplish.

Politically, this meant that rulers needed to understand their subjects—what motivates them, what they fear, how to maintain order without provoking rebellion. The sovereign who understands human psychology and social mechanics can maintain stable power. Ignorant rulers lose control.

Same principle applies more broadly. Understanding how power actually works—how institutions function, how decisions get made, how influence flows—gives you the ability to navigate these systems effectively. People without this understanding remain powerless regardless of their formal rights or abilities.

Michel Foucault: Knowledge Creates Reality

Jump forward to the 20th century. French philosopher Michel Foucault (1926-1984) developed probably the most sophisticated analysis of the knowledge-power relationship. His work remains hugely influential in understanding how modern societies function.

Foucault’s central insight: Power doesn’t just use knowledge as a tool; power and knowledge are fundamentally intertwined. You can’t separate them. Knowledge shapes what we consider true, normal, or right. And these categories determine how power operates in society.

Take psychiatry as an example (Foucault wrote extensively about this). Psychiatric knowledge defines what counts as mental illness, what behaviors are normal versus abnormal, who needs treatment. This knowledge creates categories that then get used to manage populations. People who fit certain categories get institutionalized, medicated, or otherwise controlled. The knowledge isn’t neutral description; it’s a tool for exercising power over people’s lives and identities.

Or consider sexuality (another Foucault topic). Medical and psychiatric discourse in the 19th century created elaborate taxonomies of sexual behaviors and identities—heterosexual, homosexual, various “perversions.” This knowledge production wasn’t just describing reality; it was creating new categories that shaped how people understood themselves and how institutions regulated behavior.

Foucault’s point generalizes. Whatever society accepts as “truth” determines what’s possible, what’s thinkable, what’s permissible. The powerful don’t primarily control through violence or obvious coercion (though those exist). They control by shaping what counts as knowledge, what narratives become dominant, what frameworks people use to understand reality.

Education systems, scientific institutions, media, professional expertise—all these create and certify knowledge. And this knowledge shapes how we think, what we consider normal, what options we imagine. That’s a form of power more subtle but often more effective than direct force.

For Foucault, the phrase “knowledge is power” understates things. Knowledge doesn’t just give you power; knowledge is how power fundamentally operates in modern societies. Control the discourse, shape the knowledge, define the categories—and you’ve exercised power in its most profound form.

Ali Ibn Abi Talib: The Earliest Recognition

Here’s something most Western discussions of this topic ignore: the relationship between knowledge and power was recognized much earlier in Islamic thought. Ali ibn Abi Talib (599-661), cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, appears to be the first historical figure to explicitly articulate this connection.

Ali was the fourth caliph in Sunni tradition and the first Imam in Shia Islam. He was renowned for his wisdom, eloquence, and learning. The collection Nahj al-Balagha (compiled in the 10th century) gathers his sermons, letters, and sayings.

In this text, Ali states: “Knowledge is power and it can command obedience. A man of knowledge during his lifetime can make people obey and follow him and he is praised and venerated after his death”.

This formulation predates Bacon by nearly a thousand years. Ali recognized that knowledge grants authority that persists beyond a person’s lifetime. Teachers, scholars, religious leaders—their influence extends through their intellectual legacy. People continue following their ideas long after they’re gone.

Islamic civilization during Ali’s era and the centuries following placed enormous value on learning. The Islamic Golden Age (roughly 8th-14th centuries) saw remarkable scientific, mathematical, philosophical, and literary achievements. This culture understood that knowledge was valuable not just spiritually but practically and socially.

Ali’s statement also implies that knowledge creates legitimate authority. People follow those who genuinely know things, not just those who claim authority without understanding. This contrasts with power based purely on force or heredity. Knowledge-based authority has a different quality—people obey because they recognize expertise and wisdom, not just because they’re compelled.

Modern Implications: Information Age Power

The knowledge-power relationship has transformed in the digital age. We’re living through what some call the “information revolution,” and it’s reshaping how power functions.

Information has become the primary source of value in advanced economies. Tech companies worth trillions don’t primarily own factories or resources. They control information, data, algorithms, platforms. Their power comes from knowing things—about users, markets, behaviors—and from mediating information flow.

Think about Google. Its power derives from organizing the world’s information and controlling how billions access it. Facebook (Meta) isn’t valuable because of its servers; it’s valuable because of the data it has about human social networks and behaviors. Amazon knows your purchasing habits, preferences, probably more about your life than you consciously realize.

Data has become the “new oil”—a resource that needs to be extracted, refined, and leveraged. Whoever controls data has power. This creates new forms of inequality. Digital divides aren’t just about who has internet access; they’re about who controls the infrastructure and algorithms that determine what information people see.

There’s also the democratization angle. The internet has made more information accessible to more people than ever before in history. In theory, knowledge is less gatekept now. You can learn almost anything online. Educational resources that once required expensive university enrollment are freely available.

But there’s a paradox. Information abundance creates new problems—how do you know what’s accurate? How do you develop expertise when you’re drowning in contradictory claims? Misinformation spreads faster than ever. Conspiracy theories flourish. The challenge shifts from accessing information to evaluating it, from finding knowledge to discerning truth.

This changes what kind of knowledge creates power. Media literacy, critical thinking, information evaluation—these become crucial skills. The powerful aren’t just those who have information but those who can filter, synthesize, and make sense of overwhelming data.

AI and machine learning add another dimension. These technologies can process information at scales humans can’t match. They identify patterns, make predictions, automate decisions. Whoever controls advanced AI systems has power amplified by computational capability to leverage knowledge.

Looking forward, the knowledge-power relationship will likely intensify. As economies become more knowledge-based, as information becomes more central to everything, the old phrase “knowledge is power” becomes less metaphorical and more literal. The question becomes: Who gets access to knowledge? Who controls its production and distribution? How do we prevent knowledge monopolies from creating permanent power imbalances?

Knowledge, Power, and Social Justice

There’s an ethical dimension here worth exploring. If knowledge is power, then unequal access to knowledge creates unjust power imbalances.

Education inequality perpetuates social stratification. Children born into wealthy families attend better schools, access better teachers, inherit cultural knowledge that opens doors. Meanwhile, children in poor communities often attend underfunded schools, lack enrichment opportunities, don’t receive the cultural capital that advantages their privileged peers.

This isn’t just unfortunate; it’s a mechanism that reproduces inequality across generations. Knowledge-power dynamics turn into structural injustice when some groups systematically lack access to education and information.

Same pattern globally. Developed nations have better educational systems, research institutions, information infrastructure. They produce most scientific knowledge. Developing nations often remain knowledge consumers rather than producers. This creates dependency relationships where power flows from knowledge-rich to knowledge-poor regions.

Language factors in too. Most scientific and academic knowledge gets published in English. This privileges English speakers and marginalizes knowledge produced in other languages. Entire intellectual traditions get ignored because they’re not accessible to dominant academic communities.

There are counter-movements. Open access publishing tries to make research freely available rather than locked behind paywalls. Open source software shares knowledge rather than hoarding it. Wikipedia demonstrates that collective knowledge production can work. These movements recognize that democratizing knowledge is necessary for justice.

But powerful interests resist. Pharmaceutical companies patent medicines, making life-saving knowledge proprietary. Tech companies guard their algorithms as trade secrets. Universities charge enormous tuition, treating education as a luxury good rather than a public good.

The ethical question: Should knowledge be treated as private property or as a common resource? If knowledge is power, restricting access to knowledge is a way of maintaining power imbalances. But knowledge production costs money, takes effort—how do we incentivize it while ensuring broad access?

These aren’t abstract debates. They affect whether new medicines reach poor populations, whether farmers in developing countries can access agricultural knowledge, whether students can afford education without crushing debt. The knowledge-power relationship has real consequences for real people.

FAQs About Knowledge is Power

Who originally said “knowledge is power”?

Thomas Hobbes first used the exact phrase “knowledge is power” in English in his 1668 edition of Leviathan. However, it’s commonly misattributed to Francis Bacon, who wrote a similar Latin phrase ipsa scientia potestas est (“knowledge itself is power”) in 1597. The earliest recognition of this relationship actually comes from Ali ibn Abi Talib in the 7th century, nearly a thousand years before Bacon.

What does “knowledge is power” mean in practical terms?

The phrase suggests that acquiring knowledge increases your capacity for influence, action, and success. Practically, this means education and expertise open opportunities, specialized knowledge creates professional value, understanding how systems work lets you navigate them effectively, and information provides advantages in competitive situations. It’s both advice to pursue learning and a description of how power actually operates in society.

Is knowledge really power in the modern world?

Yes, arguably more than ever. In information-based economies, knowledge and data have become primary sources of value and power. Tech companies worth trillions derive power from controlling information flow and data. However, the relationship is complex—information abundance creates new challenges in discerning truth, and access to knowledge remains unequal, creating power imbalances.

How did Francis Bacon contribute to this idea?

Bacon laid groundwork for modern science by advocating empirical observation and experimentation over reliance on ancient authorities. He argued that understanding natural laws gives humans power to manipulate nature for practical benefit. His philosophical framework emphasized that knowledge should be useful and transformative, not just contemplative. This approach became foundational for the scientific revolution and modern technology.

What was Michel Foucault’s view on knowledge and power?

Foucault argued that power and knowledge are inseparable—knowledge doesn’t just serve power, it constitutes how power operates in modern societies. Whoever defines what counts as truth, normalcy, or expertise exercises profound power. Knowledge creates categories (like mental illness, criminality, sexuality) that institutions then use to manage populations. Control over discourse and knowledge production is itself the most fundamental form of power.

Why is access to knowledge an ethical issue?

If knowledge creates power, then unequal access to education and information perpetuates unjust power imbalances. Education inequality reproduces social stratification across generations. Global knowledge disparities maintain dependency relationships between developed and developing nations. Treating knowledge as private property versus common resource has real consequences for whether people can access life-saving medicines, quality education, and opportunities for advancement.

How has the internet changed the knowledge-power relationship?

The internet has both democratized and concentrated knowledge-power. More information is accessible to more people than ever, potentially reducing gatekeeping. However, controlling algorithms, platforms, and data has created new power centers in tech companies. Information abundance creates challenges in evaluating accuracy. The shift is from accessing information to filtering and synthesizing it effectively.

What did Thomas Hobbes mean by knowledge is power?

Hobbes focused on political power—understanding human nature and social mechanics enables effective governance and institutional design. He argued the purpose of knowledge is enabling action and producing change, not contemplation for its own sake. Knowledge of how societies and people function gives leaders and individuals the ability to navigate political systems, maintain order, and achieve objectives.

Can knowledge create power without action?

Not really. Knowledge creates potential power, but it requires application to become actual power. Simply knowing things doesn’t automatically translate to influence unless that knowledge gets used—whether to make decisions, solve problems, create value, persuade others, or navigate systems. The connection between knowledge and power depends on transforming understanding into effective action.

What types of knowledge create the most power?

Different types create different power: technical knowledge enables specialized capabilities others lack; strategic knowledge about people and situations allows effective navigation of complex environments; cultural knowledge grants insider status and social advantages; information as commodity creates direct economic value; and knowledge about how power structures function enables working within or challenging those systems. The most powerful knowledge often combines multiple types.