Picture this: you’re standing somewhere on Earth—maybe in your backyard, maybe on a beach halfway around the world—and someone asks you to describe exactly where you are. “Near the park” won’t cut it. “In California” is too vague. You could give them your street address, sure, but what if you’re in the middle of the ocean, or hiking through a forest, or standing at a spot that doesn’t have a street name? This is where things get interesting. There’s actually a universal address system that works anywhere on the planet, whether you’re in downtown Tokyo, the middle of the Sahara Desert, or floating in a boat off the coast of Antarctica. It’s called the geographic coordinate system, and it uses two magical numbers—latitude and longitude—to pinpoint any spot on Earth with stunning precision. These aren’t just abstract concepts geographers dreamed up to torture students. They’re the invisible grid that makes GPS work, that helps ships navigate oceans, that lets pilots fly safely, and that ensures your pizza delivery driver finds your house. Understanding latitude and longitude isn’t just geography trivia—it’s understanding how we’ve learned to navigate our entire planet.

What Are Latitude and Longitude?

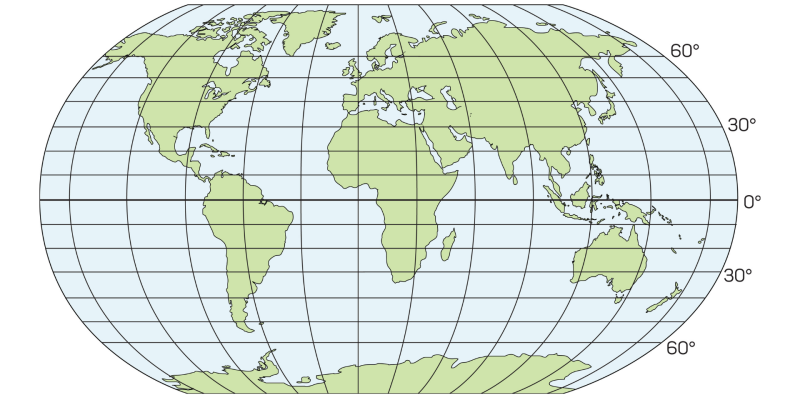

Think of Earth as a giant sphere (okay, technically it’s slightly squashed at the poles, but close enough). Now imagine wrapping this sphere in an invisible grid—horizontal lines running around it like the rings of a barrel, and vertical lines running from top to bottom like the segments of an orange. These imaginary lines create a coordinate system that lets you describe any location using just two numbers. That’s the essence of latitude and longitude.

Latitude tells you how far north or south you are from the equator. Remember the equator—that imaginary line around Earth’s middle that divides the planet into Northern and Southern Hemispheres? That’s your starting point for latitude, your zero line. If you move north from the equator, your latitude increases in a northerly direction. Move south, and it increases in a southerly direction. Latitude is measured in degrees, from 0° at the equator to 90° at the North Pole and 90° at the South Pole (though we call that one -90° or 90°S to indicate it’s south).

The lines of latitude are called parallels because they run parallel to each other—they’re like horizontal circles wrapped around Earth that never intersect. Stand anywhere on a parallel, and every other point on that same line is exactly the same distance from the equator as you are. The equator itself is the biggest parallel. As you move toward the poles, the parallels get smaller and smaller until they become just a point at each pole.

Longitude, on the other hand, tells you how far east or west you are from a specific reference line called the Prime Meridian or Greenwich Meridian (named after Greenwich, England, where it passes through). If latitude is your position on the horizontal rings, longitude is your position on the vertical segments. Longitude is measured in degrees from 0° at the Prime Meridian to 180° heading east and 180° heading west (they meet on the opposite side of the planet, in the Pacific Ocean).

The lines of longitude are called meridians, and unlike parallels, they’re not parallel to each other—they all converge at the North and South Poles, like the sections of an orange coming together at top and bottom. All meridians are the same length (they all run from pole to pole), but the distance between them varies depending on where you are—they’re farthest apart at the equator and squeezed together at the poles.

So here’s the beautiful simplicity of it all: give me any two numbers—a latitude and a longitude—and I can find exactly one spot on Earth. Give me any location on Earth, and I can describe it with exactly two numbers. It’s like every place on the planet has its own unique numerical address that works regardless of language, country, or whether humans have even named that place.

How Coordinates Are Written

Geographic coordinates are typically written in degrees (°), minutes (‘), and seconds (”)—yes, like time, because the system was developed by astronomers who were used to measuring angles in the sky, and they divided things the same way we divide hours.

Here’s how it works: each degree is divided into 60 minutes, and each minute is divided into 60 seconds. So when you see coordinates like 40° 26′ 46″ N, 79° 58′ 56″ W, that’s saying 40 degrees, 26 minutes, 46 seconds North latitude, and 79 degrees, 58 minutes, 56 seconds West longitude. That particular location, by the way, is Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

You’ll also sometimes see coordinates written in decimal degrees, which is increasingly common with digital mapping and GPS systems. Instead of minutes and seconds, the fractional part of the degree is expressed as a decimal. So Pittsburgh could also be written as 40.446111, -79.982222. Notice the negative sign? That indicates West (negative for West and South, positive for East and North in many systems). It’s simpler for computers to work with, though perhaps less intuitive for humans.

The convention is usually to write latitude first, then longitude, often in parentheses: (latitude, longitude). And you’ll see cardinal directions indicated as N/S for latitude and E/W (or sometimes O for Oeste in Spanish) for longitude. So (51° 30′ N, 0° 7′ W) is telling you this location is in the Northern Hemisphere and Western Hemisphere—which happens to be London.

The Reference Lines: Equator and Prime Meridian

Every coordinate system needs a starting point, a zero line. For latitude and longitude, those zero lines are the equator and the Prime Meridian, and the choice of where to put them has as much to do with history and politics as with geography.

The Equator: Latitude’s Zero Point

The equator was the easy one. It’s the natural midpoint between the poles, the fattest part of Earth’s belly, the line equidistant from both poles. It sits at 0° latitude and divides the planet into Northern and Southern Hemispheres. The equator is about 40,075 kilometers (24,901 miles) long—that’s Earth’s circumference at its widest point.

The equator passes through 13 countries: Ecuador (which is named after it), Colombia, Brazil, São Tomé and Príncipe, Gabon, Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Kenya, Somalia, Maldives, Indonesia, and Kiribati. If you’ve ever been to the equator, you might have visited one of those tourist spots where you can stand with one foot in each hemisphere and jump back and forth between north and south.

Being at the equator has real physical significance. The sun passes directly overhead twice a year (at the equinoxes), so there’s no shadow at noon on those days. Day and night are almost exactly equal length year-round. The climate is typically hot and humid because the sun’s rays hit most directly. And interestingly, you’re moving faster at the equator than anywhere else on Earth—about 1,670 kilometers per hour (1,037 mph)—because you’re at the widest part of the planet as it spins on its axis.

The Prime Meridian: Longitude’s Zero Point

Choosing the Prime Meridian—the 0° longitude line—was much more arbitrary and contentious. Unlike the equator, which is defined by Earth’s geometry, longitude lines are all equally valid as potential zero points. So which one do you choose?

For centuries, different countries used different prime meridians—each nation putting their own capital or major observatory at zero longitude. The French used Paris. The Spanish used Madrid. The British used Greenwich. This created chaos for international navigation and mapping. Imagine trying to use a map where the coordinates meant different things depending on who made it.

In 1884, representatives from 25 nations met at the International Meridian Conference in Washington, D.C., and after considerable debate (the French were particularly unhappy about it), they agreed to standardize on the Greenwich Meridian as the global Prime Meridian. Why Greenwich? Partly because the British Navy was the dominant naval power at the time and most shipping charts already used it. Partly because the United States had already adopted it. And partly as a compromise—the British had agreed to adopt the metric system (though they never fully did) in exchange for Greenwich becoming the Prime Meridian.

The Prime Meridian runs through Greenwich, a borough of London, specifically through the Royal Observatory. You can visit it and stand on the actual line, with one foot in the Eastern Hemisphere and one in the Western Hemisphere. There’s a brass strip marking it on the ground, and at night a green laser shoots northward along the meridian across London’s sky.

Interestingly, modern GPS systems use a slightly different reference frame, and if you check your GPS coordinates at the Greenwich line, you’ll find you’re actually about 102 meters (334 feet) east of where GPS says 0° longitude is. This is because GPS uses a more sophisticated model of Earth’s shape and center of mass, but the traditional Greenwich line is still the official Prime Meridian by international agreement.

The Prime Meridian divides Earth into the Eastern Hemisphere (from 0° to 180° E) and Western Hemisphere (from 0° to 180° W). The 180th meridian, directly opposite the Prime Meridian on the other side of Earth, is where East meets West—and it’s also roughly (with some zigzags for political reasons) the International Date Line, where the calendar date changes.

Understanding Parallels: The Horizontal Lines

Parallels are the horizontal lines of latitude that circle Earth parallel to the equator. While there are infinitely many possible parallels (you could draw one through any latitude), certain parallels have special significance because of Earth’s tilt and its orbit around the sun.

The Major Parallels

Besides the equator, five major parallels are marked on most maps:

The Tropic of Cancer sits at 23.5° N latitude (more precisely, 23°26’11” N, though this slowly changes due to Earth’s axial precession). This is the northernmost latitude where the sun can appear directly overhead. It happens once a year, at the June solstice (around June 21), marking the beginning of summer in the Northern Hemisphere. The Tropic of Cancer passes through Mexico, the Bahamas, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, China, and Taiwan, among others.

The Tropic of Capricorn mirrors it at 23.5° S latitude. This is the southernmost latitude where the sun appears directly overhead, which happens at the December solstice (around December 21), marking the beginning of summer in the Southern Hemisphere. It passes through Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil, Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Mozambique, Madagascar, and Australia.

The region between these two tropics is called, appropriately enough, the tropics. If you live within this zone, the sun passes directly overhead at some point during the year. This results in consistently warm temperatures year-round, minimal seasonal variation, and the tropical climates most of us associate with the word “tropical.”

The Arctic Circle sits at 66.5° N latitude (or more precisely, 66°33’49” N). This is the southernmost latitude in the Northern Hemisphere where you can experience 24 hours of continuous daylight (the midnight sun) in summer and 24 hours of continuous darkness (polar night) in winter. The exact latitude is defined as 90° minus Earth’s axial tilt. The Arctic Circle passes through northern Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia.

The Antarctic Circle mirrors it at 66.5° S latitude. South of this line, you experience the same phenomenon—midnight sun in summer (December) and polar night in winter (June). The Antarctic Circle mostly passes through the Southern Ocean and clips the Antarctic Peninsula.

These special parallels exist because Earth’s axis is tilted 23.5° relative to its orbital plane around the sun. This tilt is responsible for seasons, and these parallels mark the boundaries of special solar phenomena resulting from that tilt.

Why Parallels Matter

Parallels aren’t just arbitrary lines—they have real climatic and environmental significance. As you move from the equator toward the poles, several things change systematically:

Temperature decreases. The equator receives the most direct sunlight year-round, so it’s hottest. As you move toward the poles, sunlight hits at increasingly shallow angles, spreading the same amount of energy over larger areas and losing more energy passing through the atmosphere. Result: it gets colder.

Seasons become more pronounced. At the equator, there are no real seasons—temperature and day length remain relatively constant. As you move toward higher latitudes, the difference between summer and winter becomes more dramatic, both in temperature and day length.

Day length varies more. At the equator, days and nights are nearly equal year-round (about 12 hours each). As you move toward the poles, the difference between summer days (longer) and winter days (shorter) increases dramatically, until you reach the polar circles where you get 24-hour days and nights.

This is why parallels are useful for describing climate zones. Tell me your latitude, and I can make pretty good guesses about your climate, vegetation, and seasonal patterns.

Understanding Meridians: The Vertical Lines

Meridians are the vertical lines of longitude that run from the North Pole to the South Pole. Unlike parallels, which are different lengths, all meridians are the same length—about 20,003.93 kilometers (12,429.87 miles) from pole to pole.

Meridians and Time Zones

Here’s where meridians get really practical: they’re the basis for time zones. Since Earth rotates 360° in 24 hours, it rotates 15° per hour (360 ÷ 24 = 15). So in theory, every 15° of longitude represents one hour of time difference.

This is why when you fly east or west across multiple time zones, you experience jet lag—you’re moving through different meridians, and the local time changes because the sun reaches different meridians at different times as Earth rotates.

The Prime Meridian at Greenwich also defines Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), now more precisely called Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). This is the time standard the world uses—all other time zones are defined as hours ahead of or behind UTC. New York is UTC-5 (five hours behind). Tokyo is UTC+9 (nine hours ahead). When it’s noon in Greenwich, you can calculate what time it is anywhere else by knowing the longitude.

How Meridians Converge

Here’s something weird about meridians: the distance between them changes depending on where you are. At the equator, meridians are farthest apart—about 111 kilometers (69 miles) per degree of longitude. But as you move toward the poles, meridians converge, getting closer and closer together until they all meet at a single point at each pole.

This means one degree of longitude represents different distances at different latitudes. At the equator, 1° of longitude is about 111 kilometers. At 60° latitude, it’s only about 55.8 kilometers. At the poles, it’s zero—all meridians meet there, so longitude becomes meaningless (which is why polar explorers often use different coordinate systems).

This is in contrast to parallels, where one degree of latitude always represents approximately the same distance—about 111 kilometers (69 miles)—regardless of where you are. Latitude is more uniform; longitude is variable.

Absolute Position vs. Relative Position

When you’re describing where something is, you’re actually choosing between two different types of location: absolute and relative. They’re both useful, but for different purposes.

Absolute Position

Absolute position is like giving someone the exact GPS coordinates of a place. It’s precise, unambiguous, and doesn’t depend on anything else. “The Eiffel Tower is at 48°51’29.6″ N, 2°17’40.2″ E” is an absolute position. Those coordinates point to one specific spot on Earth and only that spot.

Absolute position is perfect when you need precision—navigation, surveying, mapping, scientific research, search and rescue operations. If someone gives you coordinates, you can find that exact location with GPS technology, no additional information needed. It’s the universal language of location.

The downside? Coordinates don’t give you context. “48°51’29.6″ N, 2°17’40.2″ E” doesn’t tell you anything about what’s there, what it’s near, whether it’s important, or how to get there from where you are. It’s precise but not necessarily meaningful without looking it up.

Relative Position

Relative position describes where something is in relation to something else. “The Eiffel Tower is in Paris, France, on the banks of the Seine River, northwest of the Louvre Museum.” This gives you context, relationships, and a sense of place, but it’s less precise.

We use relative position constantly in everyday life. “Turn left at the gas station.” “I live three blocks from the park.” “Mexico is south of the United States and north of Guatemala.” These descriptions help us understand spatial relationships and navigate by landmarks and directions rather than coordinates.

Relative position is also useful for understanding geography at larger scales. “The Mediterranean Sea is between Europe and Africa” tells you something about climate, culture, and history that coordinates alone wouldn’t convey.

The best geographical descriptions often combine both. “San Francisco (37.77° N, 122.41° W) is located on the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula, between the Pacific Ocean and San Francisco Bay.” Now you have precision and context.

How GPS Uses Coordinates

Every time you use GPS on your phone or in your car, you’re using the geographic coordinate system in real-time. But how does it actually work?

GPS (Global Positioning System) relies on a constellation of at least 24 satellites orbiting Earth at about 20,000 kilometers altitude. Each satellite continuously broadcasts signals containing the satellite’s location and the exact time the signal was sent.

Your GPS receiver picks up signals from multiple satellites (it needs at least four to get an accurate three-dimensional position). By calculating how long each signal took to reach you, the receiver can determine your distance from each satellite. With distances from multiple satellites, it can triangulate your exact position on Earth’s surface.

The result? Your device calculates your latitude, longitude, and altitude. These coordinates are then used to place you on a digital map, calculate routes, show you where you are relative to your destination, and guide you turn-by-turn.

Modern GPS is remarkably accurate—typically within 5-10 meters (16-33 feet) under good conditions, and even better with differential GPS or additional sensors. That’s why it can guide you to a specific address, not just the general neighborhood. It’s all thanks to the coordinate system and some very sophisticated math and engineering.

Coordinates of Major World Cities

Want to see how this works in practice? Here are the precise geographic coordinates of major cities around the world. These coordinates could guide you to the approximate city center or a major landmark in each location:

Europe

London, England: 51° 30′ 26″ N, 0° 7′ 39″ W

Paris, France: 48° 51′ 24″ N, 2° 21′ 8″ E

Berlin, Germany: 52° 31′ 12″ N, 13° 24′ 18″ E

Madrid, Spain: 40° 25′ 0″ N, 3° 42′ 9″ W

Rome, Italy: 41° 53′ 24″ N, 12° 29′ 32″ E

Amsterdam, Netherlands: 52° 22′ 23″ N, 4° 53′ 32″ E

Moscow, Russia: 55° 45′ 8″ N, 37° 37′ 6″ E

Istanbul, Turkey: 41° 0′ 49″ N, 28° 57′ 18″ E

Americas

New York City, USA: 40° 42′ 46″ N, 74° 0′ 22″ W

Washington, D.C., USA: 38° 54′ 17″ N, 77° 0′ 33″ W

Mexico City, Mexico: 19° 25′ 42″ N, 99° 7′ 40″ W

Lima, Peru: 12° 2′ 36″ S, 77° 1′ 43″ W

Buenos Aires, Argentina: 34° 36′ 12″ S, 58° 22′ 54″ W

São Paulo, Brazil: 23° 32′ 59″ S, 46° 38′ 10″ W

Asia and Oceania

Tokyo, Japan: 35° 41′ 22″ N, 139° 41′ 30″ E

Beijing, China: 39° 54′ 20″ N, 116° 23′ 29″ E

Hong Kong, China: 22° 16′ 42″ N, 114° 9′ 32″ E

New Delhi, India: 28° 36′ 36″ N, 77° 13′ 48″ E

Bangkok, Thailand: 13° 45′ 9″ N, 100° 29′ 38″ E

Sydney, Australia: 33° 51′ 54″ S, 151° 12′ 20″ E

Wellington, New Zealand: 41° 17′ 20″ S, 174° 46′ 37″ E

Africa and Middle East

Cairo, Egypt: 30° 2′ 40″ N, 31° 14′ 9″ E

Cape Town, South Africa: 33° 55′ 31″ S, 18° 25′ 26″ E

Nairobi, Kenya: 1° 17′ 11″ S, 36° 49′ 2″ E

Dubai, UAE: 25° 15′ 47″ N, 55° 18′ 0″ E

Notice how Northern Hemisphere cities have N (north) for latitude, Southern Hemisphere cities have S (south), cities west of Greenwich have W (west) for longitude, and cities east of Greenwich have E (east). The numbers tell the story of each city’s position on our planetary grid.

Practical Uses of Latitude and Longitude

The coordinate system isn’t just for geographers and navigators anymore. It touches almost every aspect of modern life:

Navigation and transportation: Ships, airplanes, cars with GPS, hiking trails, delivery services—all rely on coordinates for routing and positioning.

Emergency services: When you call 911 (or your local emergency number) from a mobile phone, your coordinates help dispatchers locate you quickly, which can save lives.

Weather forecasting: Meteorologists use coordinates to precisely locate weather systems, track storms, and issue location-specific forecasts and warnings.

Scientific research: Ecologists studying wildlife, geologists mapping rock formations, oceanographers tracking currents, climate scientists monitoring change—all use coordinates to record where data was collected.

Real estate and property: Property boundaries are legally defined using coordinates, ensuring precise definitions of who owns what land.

Social media and photography: When you geotag a photo or check in at a location, you’re adding coordinate data to that content.

Archaeology and paleontology: Recording exact locations of discoveries is crucial for understanding context and conducting further research.

Military and defense: Precision targeting, troop positioning, and strategic planning all rely heavily on coordinate systems.

Astronomy: Even looking up at the stars involves coordinates—astronomers use a celestial coordinate system analogous to latitude and longitude to map the sky.

Beyond Earth: Coordinates on Other Worlds

Here’s a fun thought: the same principle of latitude and longitude can be applied to any spherical body. We use areographic coordinates on Mars (with the Prime Meridian defined as passing through a small crater called Airy-0). We use selenographic coordinates on the Moon. Even planets and moons that we’ve only explored with spacecraft have coordinate systems defined so we can map their surfaces and navigate rovers.

The beauty of the system is its universality—once you understand latitude and longitude on Earth, you understand the fundamental principle that can locate any point on any sphere anywhere in the universe.

FAQs About Latitude and Longitude

What’s the difference between latitude and longitude?

Latitude measures how far north or south you are from the equator, while longitude measures how far east or west you are from the Prime Meridian (which runs through Greenwich, England). Think of it this way: latitude lines (parallels) run horizontally around Earth like rings around a barrel, while longitude lines (meridians) run vertically from North Pole to South Pole like segments of an orange. Latitude ranges from 0° at the equator to 90° at the poles (labeled N or S). Longitude ranges from 0° at the Prime Meridian to 180° heading east or west (labeled E or W). Together, these two measurements can pinpoint any location on Earth’s surface. A simple memory trick: “lat is flat” (latitude lines are horizontal) and “long are long” (longitude lines run the long way from pole to pole).

Why is Greenwich the Prime Meridian?

Greenwich became the Prime Meridian through international agreement in 1884, chosen largely for practical and political reasons rather than scientific necessity. Unlike the equator (which is naturally defined by Earth’s geometry), any meridian could theoretically serve as the zero point for longitude. Different countries historically used different prime meridians, creating confusion in navigation and mapping. At the 1884 International Meridian Conference, 25 nations agreed to standardize on Greenwich for several reasons: the British Royal Navy was the dominant naval power and most nautical charts already used Greenwich; the United States had adopted it; and it offered a compromise (Britain agreed to consider adopting the metric system in exchange). The line passes through the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, where you can visit and literally stand on the Prime Meridian. Interestingly, modern GPS actually places 0° longitude about 102 meters east of the traditional Greenwich line due to more sophisticated Earth modeling, but Greenwich remains the official Prime Meridian by convention.

How do you read geographic coordinates?

Geographic coordinates are typically written as latitude first, then longitude, with each expressed in degrees (°), minutes (‘), and seconds (”). For example, 40° 26′ 46″ N, 79° 58′ 56″ W means 40 degrees, 26 minutes, 46 seconds North latitude, and 79 degrees, 58 minutes, 56 seconds West longitude. The letters N/S indicate whether latitude is north or south of the equator, and E/W indicate whether longitude is east or west of the Prime Meridian. You might also see coordinates in decimal degrees format: 40.446111, -79.982222, where negative values indicate south (for latitude) or west (for longitude). Both formats represent the same location—Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—just expressed differently. When speaking coordinates aloud, you’d say “forty degrees, twenty-six minutes, forty-six seconds north; seventy-nine degrees, fifty-eight minutes, fifty-six seconds west.” The convention of latitude first helps avoid confusion, though you should always double-check which number is which when entering coordinates into GPS devices.

What are parallels and meridians?

Parallels and meridians are the imaginary lines that create Earth’s coordinate grid. Parallels are horizontal lines running east-west that circle Earth parallel to the equator—that’s why they’re called parallels. They measure latitude and range from the equator (0°) to the poles (90° N and 90° S). Important parallels include the Tropic of Cancer (23.5° N), Tropic of Capricorn (23.5° S), Arctic Circle (66.5° N), and Antarctic Circle (66.5° S), each marking significant climatic zones. Meridians are vertical lines running north-south from pole to pole that measure longitude. Unlike parallels, meridians aren’t parallel to each other—they converge at both poles like the segments of an orange. The most important meridian is the Prime Meridian (0°) at Greenwich, which divides Earth into Eastern and Western Hemispheres. Together, parallels and meridians create a grid that allows any location on Earth to be precisely identified by its latitude and longitude coordinates.

How accurate is GPS?

Modern GPS is typically accurate to within 5-10 meters (16-33 feet) under good conditions, though accuracy varies based on several factors. Consumer GPS devices (like your smartphone) use signals from multiple satellites in the Global Positioning System constellation to calculate your position. Accuracy improves when your device can “see” more satellites (at least 4 needed for 3D positioning) and degrades when satellites are blocked by buildings, trees, or terrain—which is why GPS often works poorly indoors or in urban canyons between tall buildings. Differential GPS (DGPS), which uses ground-based correction stations, can achieve accuracy of 1-3 meters. Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) GPS used in surveying and precision agriculture can achieve centimeter-level accuracy. Weather conditions, satellite geometry, and signal interference also affect accuracy. Your smartphone GPS is typically less accurate than dedicated GPS devices because phones prioritize battery life and processing power. The U.S. military has access to more precise GPS signals, while civilian signals are intentionally less accurate (though still very useful). Despite limitations, GPS accuracy is remarkable considering you’re determining your position on a planet using satellites 20,000 kilometers above you.

Can latitude and longitude be negative?

Yes, latitude and longitude can be expressed as negative numbers, particularly when using decimal degree format. The convention is: positive numbers indicate North latitude and East longitude, while negative numbers indicate South latitude and West longitude. So instead of writing “34° 36′ 12″ S, 58° 22′ 54″ W” for Buenos Aires, you could write “-34.603333, -58.381667” where both negative signs tell you the location is in the Southern and Western Hemispheres. This negative number system is especially common in computer programming, databases, and digital mapping applications because it’s simpler for computers to work with signed numbers than letter designations. When you see coordinates without N/S/E/W letters, assume positive values are North and East, negative values are South and West. However, when using the traditional degrees-minutes-seconds format, you’ll typically see cardinal direction letters (N/S/E/W) rather than positive/negative signs. Both methods work—they’re just different conventions for expressing the same information, with negative numbers being more computer-friendly and cardinal letters being more human-readable.

What happens to longitude at the poles?

Longitude becomes meaningless at the exact North and South Poles because all meridians converge there. Think about it: meridians are lines that run from pole to pole, so at the poles themselves, every meridian meets. If you’re standing precisely at the North Pole, you’re simultaneously at every longitude—0° through 180° E and W all at once. There’s no “east” or “west” at the poles because every direction is south (from the North Pole) or north (from the South Pole). This creates problems for traditional latitude-longitude navigation. Polar explorers and scientists working in polar regions often use alternative coordinate systems like Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) or Polar Stereographic projections that handle polar regions more sensibly. Latitude still works fine at the poles—the North Pole is 90° N and the South Pole is 90° S—but longitude breaks down. This is why if you look at GPS coordinates at the poles, they might jump erratically or show strange values. It’s not that GPS doesn’t work there (though satellite coverage can be spotty), it’s that the coordinate system itself has a singularity at those points where the math breaks down.

Why are there 360 degrees in a circle?

You might wonder why we divide circles—and Earth’s coordinate system—into 360 degrees rather than, say, 100 or 1,000. The 360-degree system comes from ancient Babylonian mathematics, dating back over 4,000 years. The Babylonians used a base-60 number system (sexagesimal), possibly because 60 has many divisors (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20, 30, 60), making it convenient for fractions and calculations without decimals. They may have also been influenced by approximating the solar year as 360 days and associating each day with one degree of the sun’s apparent annual journey around the sky. The system stuck because it’s remarkably practical: 360 is divisible by many numbers, making it easy to work with common fractions like halves (180°), thirds (120°), quarters (90°), sixths (60°), and so on. Greek mathematicians adopted it from the Babylonians, and it became standard in astronomy, navigation, and eventually geography. By the time the modern coordinate system was formalized, the 360-degree circle was so entrenched that using anything else would have been impractical. We also inherited from the Babylonians the division of each degree into 60 minutes and each minute into 60 seconds, which is why time and angles use the same units—they share Babylonian mathematical heritage.

How were coordinates determined before GPS?

Before GPS, determining coordinates required celestial navigation—observing the sun, stars, and planets to calculate position. For latitude, ancient navigators used tools like the astrolabe, sextant, or quadrant to measure the angle of the North Star (Polaris) above the horizon at night, or the sun’s altitude at noon. The angle directly corresponds to your latitude—if Polaris is 40° above the horizon, you’re at 40° N latitude. In the Southern Hemisphere where Polaris isn’t visible, navigators used other stars or the sun. Longitude was much harder and became one of history’s great scientific challenges. You need to know what time it is at a reference location (like Greenwich) and compare it to local time (determined by sun position). Since Earth rotates 15° per hour, time differences reveal longitude. But this required accurate clocks (chronometers) that could keep time precisely during long sea voyages—a problem finally solved by John Harrison in the 18th century with his marine chronometers. Land surveyors used theodolites and triangulation, carefully measuring angles and distances from known reference points. Creating accurate maps took years of painstaking observation and calculation. GPS revolutionized everything by making what once required expert skills and expensive instruments available to anyone with a smartphone, giving positions in seconds that would have taken hours of calculations to determine historically.

Can coordinates change over time?

Surprisingly, yes—coordinates of fixed locations can change slightly over time due to several factors. The most significant is continental drift (plate tectonics). Earth’s tectonic plates move continuously, typically 2-10 centimeters per year. Over decades, this adds up. For example, Hawaii moves about 7 centimeters northwest each year, so its coordinates slowly change. Europe and North America drift apart by about 2.5 cm annually. For most purposes this is negligible, but for precision surveying and scientific applications, it matters. Modern coordinate systems like WGS 84 (used by GPS) are defined relative to Earth’s center of mass and account for plate motion. Additionally, Earth’s axis wobbles slightly (precession and nutation), causing tiny coordinate changes. The exact positions of the poles shift slightly over time. Earthquakes can suddenly shift land, dramatically changing coordinates in affected areas—the 2011 Japan earthquake moved parts of Japan several meters. Ground subsidence or uplift from groundwater extraction, oil drilling, or post-glacial rebound also causes coordinate changes. For everyday navigation, these changes are too small to notice, but geodesists and surveyors must account for them. This is why high-precision coordinate systems include a “reference epoch” specifying when the coordinates were accurate, and coordinates may need updating over time to remain precise.

What’s the most remote location on Earth by coordinates?

The most remote location depends on how you define “remote.” Point Nemo (48°52’36” S, 123°23’36” W) is the oceanic pole of inaccessibility—the point in the ocean farthest from any land. It’s in the South Pacific Ocean, about 2,688 kilometers (1,670 miles) from the nearest lands (Ducie Island, Motu Nui, and Maher Island). Point Nemo is so isolated that the nearest humans are often astronauts aboard the International Space Station passing overhead—the ISS orbits at about 400 km altitude, closer than any land. This extreme remoteness makes Point Nemo the designated spacecraft cemetery where space agencies deliberately crash deorbiting satellites and space stations so debris lands harmlessly in empty ocean. On land, the Eurasian Pole of Inaccessibility (46°17′ N, 86°40′ E) in northwestern China, about 2,645 km from the nearest ocean, is the point farthest from any coastline. For inhabited places, Tristan da Cunha (37°6’44” S, 12°16’56” W) is often called the most remote inhabited archipelago—2,816 km from South Africa and 3,360 km from South America, with only about 250 residents and no airport. These coordinates represent the edge of human civilization, the ultimate middle of nowhere.