We explain what the main Aztec gods were, the characteristics of each one, their origin and various myths and rituals.

What were the main Aztec gods?

The Aztecs, also called Mexicas, They constituted one of the most important Mesoamerican civilizations of the late Postclassic period (1325-1521). They settled in the central region of Mesoamerica, where they founded the city of Mexico-Tenochtitlán (present-day Mexico City), and became the most powerful state in the region, known as the Aztec Empire, Mexica Empire or Tenochca Empire.

This empire was governed by the so-called Triple Alliance, of which the Mexica were part along with their allies from Texcoco and Tlacopan. However, the Mexica ended up leading the alliance and, by the time of the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in Mesoamerica in the 16th century, the empire was clearly administered from Tenochtitlán.

The Aztecs were a Nahua tribe with their own identity, with their beliefs and divinities which they took with them on their march towards the Valley of Mexico in the 14th century. Although they were originally nomads, in just two hundred years they formed one of the most important empires in pre-Columbian America.

As they conquered and subjugated peoples, they came into contact with a broad Mesoamerican cultural heritage, which they integrated into their own culture. In this way, the Aztec religion developed, a religion polytheistic with a strong warrior component in which human sacrifices were frequent.

Below is a list of the main gods that the Mexica worshiped. Some of them were specifically Aztec gods, while others were divinities from other Mesoamerican cultures that they incorporated into their pantheon and mythology.

See also: Mesoamerican cultures

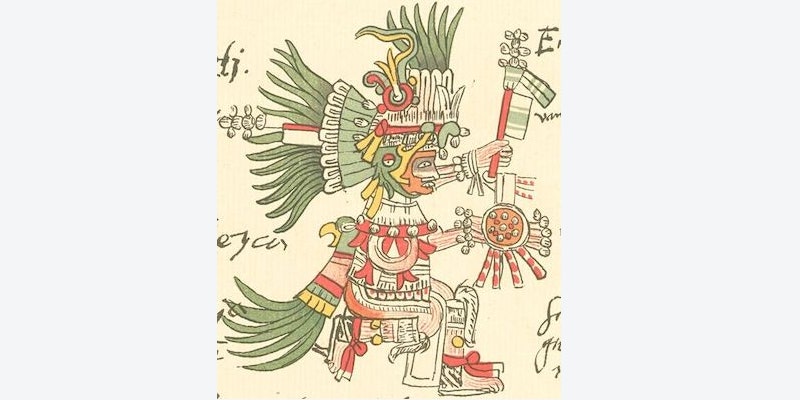

Huitzilopochtli

The main deity of the Mexica religion was Huitzilopochtli, solar god of the war whose cult reached the Valley of Mexico and the central Mesoamerican highlands along with the Mexica. By the time the Spanish arrived, his cult was widespread among some peoples subject to the Aztec Empire.

Its name can be translated as “southern hummingbird” or “left hummingbird”, and its main temple was in Huitzilopochco (current Churubusco, in the south of Mexico City). The festivals in his honor were celebrated by the Aztecs once a year under the name of panquetzaliztli and included human sacrifices.

According to the myth, Huitzilopochtli ordered the Aztecs to march from the north of present-day Mexico towards the southern lands, that is, towards what later became Tenochtitlán. His instruction was to advance until they found an eagle on a cactus, since that would be the sign that would mark the place where they would settle. They did so and founded Tenochtitlán. For this reason, this image is found today on the shield and flag of Mexico.

One of the myths of Huitzilopochtli's birth presents him as the son of the earthly goddess Coatlicue, despised by his four hundred older brothers (the stars of the south) and his sister Coyolxauhqui, who set out to kill Coatlicue. But Huitzilopochtli was born armed and easily defeated his brothers. Later, he took the severed head of his sister Coyolxauhqui and threw it into the sky, where it became the Moon, while Huitzilopochtli remained associated with the Sun.

Despite the enormous importance that Huitzilopochtli had for the Mexica, Not many representations of this god survive. It is believed that this is because his image used to be carved in wood, a more perishable material than stone. Furthermore, since it was a god originally from the Mexica, it had no equivalents in the gods of other Mesoamerican civilizations.

Quetzalcoatl

One of the great gods shared by almost all the peoples of Mesoamerica and one of the main gods of the Mexica pantheon was Quetzalcóatl. It was considered the god of light, fertility, winds, creation and knowledge associated with the color white.

Its name translates as “feathered serpent,” and that was the most common way to represent it: the snake symbolized the earthly aspect and the feathers symbolized the heavenly or spiritual principles.

In Aztec mythology, Quetzalcoatl He was one of the four primal gods (along with Tezcatlipoca, Huitzilopochtli and Xipe Tótec), children of the gods Ometecuhtli and Omecíhuatl (male and female parts of a single dual divinity called Ometéotl).

It also had a presence in the Toltec, Olmec, Mayan, Pipil and Teotihuacan religions, among others. Its dragon-like form can be found in ruins and fragments from very different regions of Mesoamerica.

Tlaloc

Known as Chaac by the Mayans, Tláloc was the god of water and rain whom the Mexica held responsible for the fertility of the soil, but also for the storms and earthquakes that caused destruction. Like many other Mesoamerican deities, Tláloc met contradictory conditions: He could be a generous and life-giving god, but also a destructive and annihilating god. Lightning, floods, frosts and droughts were also attributed to him.

They honored him during the first month of each new year, and his cult was also practiced by the Teotihuacans, the Toltecs, the Mayans, the Totonacas, the Tlaxcalans and other Mesoamerican peoples, since it was one of the oldest deities of Mesoamerica. He was frequently represented with a blue or black face, sometimes green, as these colors symbolized nature and water. In addition, symbols representing drops of water were often painted on their dresses.

The festivities in honor of Tláloc were celebrated with marches to the sacred peaks, among dancing people and sacrifices of children beautifully decorated, lying on stretchers with flowers and feathers. Her tears along the way were interpreted as good omens of abundant rains. Once at the top, the priests of Tláloc proceeded to sacrifice them to offer them to the god. According to some sources, their hearts were ripped out, but others mention that they were drowned or their throats slit.

Tezcatlipoca

Tezcatlipoca was a god from Toltec mythology, but shared by many Mesoamerican peoples, including the Aztecs. It was him god of providence, the invisible, darkness and creation. Together with Huitzilopochtli, Quetzalcóatl and Xipe Tótec, they made up the four creator gods, descendants of the original couple formed by Ometecuhtli and Omecíhuatl (that is, the dual divinity Ometéotl).

To Tezcatlipoca He was depicted with one or more black stripes on his face and often with an obsidian mirror on the chest or instead of the left foot, in which human actions and thoughts could be seen reflected and from which smoke could emerge. It was associated with the northern part of the universe, with the night and with all material things. One of its symbols was the obsidian knife.

He was also the lord of the natural world and opposed the spirituality of the luminous Quetzalcoatl, which is why he was associated with the color black. In some versions of the myth, both brothers fought each other.

On the other hand, Tezcatlipoca He was a god of war and the patron saint of warriors. The festivals in his honor were the second in importance for the Aztecs, after those dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. On these occasions, a prisoner of war was taken and treated as a nobleman for a year, in preparation for his ritual sacrifice, carried out after walking the streets of the town to the rhythm of a flute. Finally, in a temple in Tenochtitlán, four flutes were broken and the heart was extracted with an obsidian knife.

Coatlicue

Goddess of fertility, guide of rebirth and mother of Huitzilopochtli, Coatlicue was commonly revered as Tonantzin (mother of the gods) . She was represented as a woman with sagging breasts who wore a skirt made of snakes and a necklace of human hands and hearts. She was married to Mixcóatl, god of storms.

According to the myth, She was the mother of four hundred gods that represented the stars of the south. One day, while she was sweeping her temple, a ball of feathers fell from the sky and she picked it up. When he placed her on his chest, she became pregnant. So gave birth to Huitzilopochtli. This offended her children, who, instigated by her daughter Coyolxauhqui, decided to murder their mother. However, they did not succeed: they were all killed by the newborn Huitzilopochtli.

Ehecatl

Ehécatl was a god shared by several Mesoamerican cultures, including the Mexica. It was associated with the wind and was described as one of the manifestations of the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl.

It was identified with the cardinal points, the vital breath of living beings and the breeze that carried the rain to favor agriculture, so that He was a fundamental god in creation myths. Furthermore, according to Aztec mythology, the movement of the Sun and Moon was due to its breath, since it was said that originally these stars were fixed in the sky.

Another story about Ehécatl stated that he had convinced a young goddess to accompany him to earth, where they both embraced each other in the shape of two branches of a tree until the young woman's grandmother discovered them and ordered the young woman's branch to be destroyed. Ehécatl gathered his remains and buried them, and from there the maguey plant was born.

He was represented with a mask with a red beak and a snail on his chest and it was venerated in circular temples, probably because, unlike the typical pyramidal temples with a rectangular plan, they offered less resistance to the wind.

Mixcoatl

Also known among the Tlaxcalans as Camaxtli, Mixcóatl was the Mexica god of storms, hunting, stars and war father of Quetzalcóatl and husband of Coatlicue.

The Aztecs believed that the Milky Way was one of its manifestations and, since he was a patron god of the Otomi and Chichimecas, he was considered a foreign god. In general, it is not easy to distinguish the cult of Mixcóatl from its variants, since various peoples honored similar deities with other names.

Mixcóatl was represented with white and red stripes on his body, and generally with hunting equipment (bow, arrows and a net). Also It was associated with the introduction of fire among human beings and, on certain dates, the Aztecs held festivals in their honor that included hunting, lighting a fire to roast meat, and sacrificing a man and a woman.

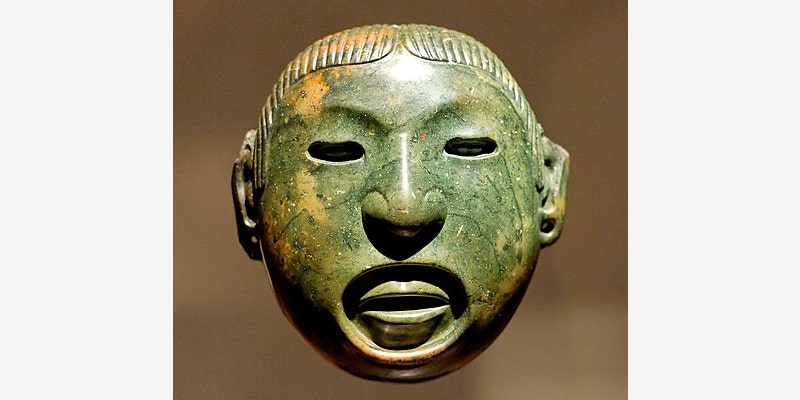

Xipe Totec

Deity of life, death, rebirth and spring Xipe Tótec's name can be translated as “our lord the skinned one.” Was associated with agriculture, vegetation, youth and corn which the god made grow by invoking the rain with his chicahuaztlia percussion musical instrument. He was also the patron saint of goldsmiths and caused some diseases.

Xipe Totec embodied the idea of the regeneration of nature of the need to get rid of the old to make room for the new, of the change of the seasons and the transition from dry soil to fertile land. This was represented in the skinning of the sacrificial victims offered to Xipe Tótec, whose skin was used as clothing by the god, which evoked the renewal or “change of skin” of nature.

This deity was shared by the Aztecs with other peoples, such as the Zapotecs and the Yopes. In the Mexica cosmogony, Xipe Tótec He was one of the primal and creative gods son of the primal couple Ometecuhtli and Omecíhuatl (that is, of the dual deity Ometéotl).

Ometeotl

God of creation in Mexica mythology, Ometéotlera understood as a double god: Ometecuhtli (“two lords” in Nahuatl) and Omecíhuatl (“two ladies” in Nahuatl). This masculine and feminine duality represented the primal couple that gave birth to the four gods of creation called “the four Tezcatlipocas” and each associated with a color: Tezcatlipoca (black), Quetzalcóatl (white), Huitzilopochtli (blue) and Xipe Tótec (red). Absolutely everything came from this creation.

It was also known as Nahuaque Tloque (“master of the near and the far”) and as Moyocoyatzin (“the creator of himself”). It was considered by the Mexicans as the creator and organizer of all things that exist. Being a god of a rather metaphysical and ancient character, he lacked temples in the Aztec Empire.

Continue with: Mayan gods

References

- AA.VV. (2024). Archeology and History. The Aztecs(53).

- Cartwright, M. (2020). 15 Aztec Gods. World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/

- López Austin, A and López Luján, L. (2001). The indigenous past. Economic Culture Fund and The College of Mexico.

- Taube, K. (1997). Aztec and Mayan Myths. University of Texas Press.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2023). Aztec Religion. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/