We explain what the low Middle Ages was, what was its society and innovations. In addition, its characteristics, trade and more.

What was the low Middle Ages?

The Middle Ages was A period of European history which extended from the 5th century until the fifteenth century. It is usually divided into:

- High Middle Ages . From the 5th century until the 10th century.

- Full Middle Ages . From the eleventh century to the thirteenth century.

- Low Middle Ages . From the fourteenth century to the fifteenth century.

In general, the Middle Ages It was characterized by a fragmentation of political power and military as a consequence of the fall of the Roman Empire. It was also a time when the feudal economic system predominated.

But in its final phase, known as the low Middle Ages, more centralized state powers began to establish It was declining the dependence on feudalism and a series of social, technological and ideological changes that gave way to the Modern Age was consolidated. Some historians consider that the low Middle Ages began in the eleventh century, and reject the term full middle ages.

- See also: Medieval culture

The historical context

During the Middle Ages (between the XI and XIII centuries), Western Europe lived a stage of economic growth . This was largely due to technical and technological innovations in the field (rotations, triennial rotation, plow improvements, mills), which allowed producing productive surpluses. These surpluses promoted, in turn, trade and artisanal production in cities.

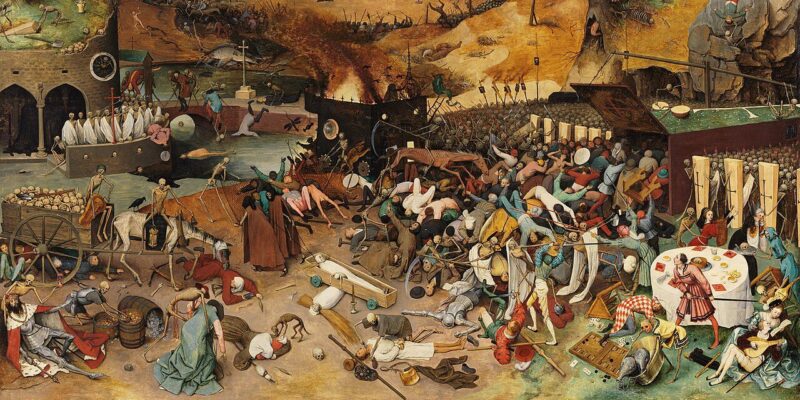

However, In the fourteenth century a series of factors were combined that transformed some aspects of social life economic and intellectual of Europe. Perhaps the most relevant was the succession of epidemics and famine that affected a large part of the European population (and, in some cases, also of Asia and North Africa), and that caused many deaths, such as the great famine (1315-1317), due to bad climatic conditions that caused bad harvests and losses of cattle of cattle (1347-1352), which claimed the life of at least one third of the inhabitants of Europe.

To these calamities other facts were added, such as intermittent conflicts of the War of the Hundred Years (1337-1453) which faced the crowns of France and England, or the revolts of peasants against tax pressure, violence and looting derived from the war.

This succession of events generated a demographic decrease that fostered:

- The improvements in the working conditions of some peasant populations (due to the decrease of labor in the field).

- The abandonment of servitude (which was the main work modality of the feudal regime).

- The migrations from the countryside to the city.

- The growth of the urban bourgeoisie and commercial, artisanal and financial activities.

- A relative decrease in the power of the feudal nobility.

- A progressive political centralization of royal crowns, based on the financing of bankers and in the service of new bureaucrats from the bourgeoisie.

- See also: centralized monarchies

Urban life in the Low Middle Ages

During the first centuries of the Middle Ages, the urban centers, which existed in Europe since the times of the Roman Empire, they decayed to become mere administrative centers . This stage was characterized by an almost absolute ruralization of the economy (with the exception of some Italian cities).

However, From the end of the eleventh century the cities began to grow again Because of the demographic increase, agricultural innovations that allowed greater productive surpluses, and the demand for artisanal products made in cities, such as fabrics or tools. This in turn encouraged short and long distance trade.

At the end of the thirteenth century, the Large cities (such as Venice, Florence, Milan, Paris or London) came to house about 100,000 inhabitants . However, most of the medieval cities probably were the 5000 inhabitants. In these years, some cities achieved the formation of an autonomous government, with its own municipal ordinances. Leagues or confederations of cities were also formed for commercial and defensive purposes (such as the Hanseatic League of Northern Germany and surroundings).

Although the famine and epidemics of the fourteenth century affected both the countryside and the cities, the migrations of peasants to urban enclosures gradually contributed to the demographic increase in these spaces. Besides, In the cities, workshops and artisan guilds were formed which allowed the corporate organization (by trades) of the workers (especially from the thirteenth century).

Urban markets made the currency more and more circulate and They enriched many merchants (especially from northern Italy) which began to act as bankers or financiers. These bourgeois were dedicated to offering loans or buying positions from the monarchs, who could form armies and centralized bureaucratic devices (on whose basis the modern states were later constituted).

The architecture of the Low Middle Ages

Medieval architecture stood out mainly for Military works (castles), civilians (palaces or municipalities) and religious (especially cathedrals) . Some of the most notable specimens correspond to the full Middle Ages and the low Middle Ages, when the resurgence of the cities promoted the construction of large buildings for municipal institutions and the nascent universities.

The most characteristic architectural style of the low Middle Ages was the Gothic which derived from Romanesque art. It emerged in northern France and then expanded to most of Europe. It was especially used in the construction of large cathedrals, between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries, such as Notre Dame in Paris (France) or that of Santa María in Burgos (Spain).

Among the most representative characteristics of this style are the pointed arc (also called ogival), the cruise vault (also called the ribs), the exterior arbotants or buttresses, the large stained glass windows, and the height and verticality of its ships and towers.

Agricultural innovations and wind mills

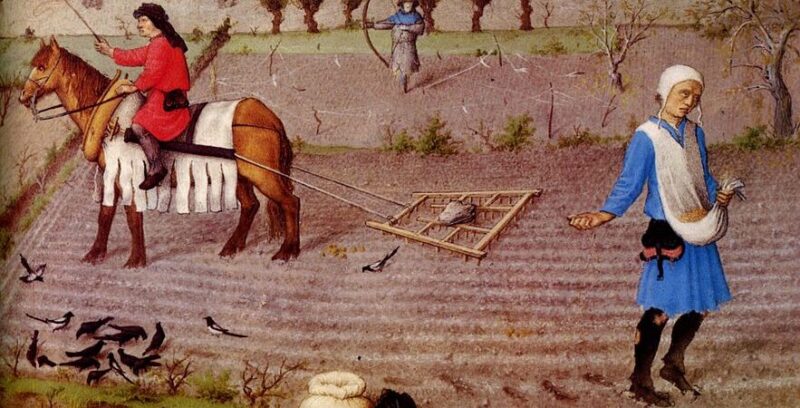

In the XI and XII centuries A new plowing form began to be used To open grooves and remove the ground before sowing the seeds. The plow of wheels and verteers (which allowed to guide the groove as a rudder) reduced the effort and improved the result with respect to the plow inherited from antiquity.

In addition, in the low Middle Ages they spread IMPROVEMENTS IN HORS which allowed the replacement of horses as shooting animals.

Another innovation in agriculture that was implemented during the middle of the Middle Ages and the low middle ages was The triennial rotation : On each plot of land, for two years different cereals were sown and a third year left the land without sowing, a period called “fallow.” As the cultivable land was divided into three plots, each plot fulfilled a different stage of the process. This significantly increased land productivity, and the quality and quantity of crops, especially in France, England, Netherlands and Germany.

An important innovation was the wind mill: a tower -shaped stone structure with wooden blades system covered with cloth. The wind mills were introduced in Europe in the XI and XII centuries and they spread especially since the fourteenth century.

These mills They used the wind, that is, wind energy to move a gear that could be used to grind cereal grains or pump water. The grains of the cereals were grinding to make flour, a task that was previously done by hand with a mortar or using water mills. With wind mills, this task was performed much faster and in large quantities, and also did not depend on water courses, so they could be built in disparate areas.

Commerce and travel

The technical and technological innovations in the agriculture of the Middle Ages allowed to increase production and allocate the productive surpluses to artisanal production and trade . This enriched urban bourgeoisies, which in some cases became lenders and bankers.

On this basis, in the low Middle Ages there was what some historians call “commercial revolution.” This term refers to changes that took place from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, such as the formation of commercial companies, new forms of credit for commercial expeditions and the consolidation of Guildas (Cities merchants corporations, similar to artisan unions). These guildas and commercial cities were sometimes linked in leagues or confederations, such as the Hanseatic League.

These changes benefited some bourgeois families from commercial cities such as the Medici in Italy or the Fugger in Germany, who obtained monopolistic rights and became great bankers. In addition, the low Middle Ages was characterized by the extension of the routes and exchange volumes: cities such as Venice, Genoa and Pisa competed for the control of the Mediterranean, while the merchants of Flanders manufactured wool fabrics for export.

The search for exotic goods (such as those that came from Asia), the circulation of stories such as Marco Polo (c. 1254-1324) and the Nautical innovations of the time, in turn motivated exploration trips That, at the beginning of the Modern Age, they allowed the Portuguese to reach southern Africa and then to India, and the Spaniards cross the Atlantic.

The decline of feudalism

During most of the Middle Ages, The economy was governed by the feudal system : the “feudal lords” (kings or nobles) gave portions of their lands (“fiefs”) to their vassals, who owe them in return fidelity and obligations (generally military). In addition, the lands used to be worked by servants, who were tied to the earth and had to pay income to the feudal lord.

From the fourteenth century, demographic changes were given because of deaths from famine, epidemics and wars. This caused a relative weakening of the feudal nobility in Western Europe, since the shortage of peasant labor allowed the demand for better working conditions and the abandonment of servitude. In turn, the growing impulse of the urban bourgeoisie and the tendency to political centralization of European monarchies determined the decline of the feudal system.

- Feudalism

The Catholic Church and the Schism of the West

During the low middle ages, The Church crossed a series of conflicts with secular powers . However, the most significant was the one that resulted in the Schism of the West (1378-1417), whereby there were two (and up to three) potatoes of the simultaneous Catholic Church.

In France, King Felipe IV had decided to impose taxes on ecclesiastical goods which caused a conflict with the Pope, Bonifacio VIII, who threatened to excommunicate him. The king’s response was to send some mercenaries to Italy to arrest him. These found and hit the Pope in the town of Anagni, but they had to free him.

When he was anointed Pope Clemente V, of French origin, changed its headquarters from Rome to Aviñón in France. This Pope and his successors were considered by some cardinals too servile to the French monarchs. In 1377, the then Pope Gregory XI returned to Rome but died the following year, and the conclave that should choose the new Pope was held in the midst of tumults of the Roman population who claimed the choice of an Italian Pope. The differences between the cardinals caused two popes to be chosen, Urban VI, who remained in Rome, and Clemente VII, which was installed in Aviñón.

This situation caused the different kingdoms of Europe to recognize one pope, until The unity of the Catholic Church based in Rome was restored in 1417 . Some historians consider that these episodes influenced some loss of legitimacy of the Church, which led to phenomena such as humanistic thinking and Protestant reform. In these years, new movements considered heretics were also persecuted, such as Bohemian spindles, Jan Hus followers (who was burned at the bonfire in 1415).

- Crusades

- Medieval era

- Medieval philosophy

References

- Álvarez Palenzuela, VA (coord.) (2002). Universal History of the Middle Ages. Ariel.

- García de Cortázar, Ja & Sesma Muñoz, Ja (2014). Medieval History Manual. Alliance.

- Hunt, L., Martin, Tr, Rosenwein, BH & Smith, BG (2016). The Making of the West. Peoples and Cultures. 5th Edition. BEDFORD/ST. Martin’s.

- Britannica, Encyclopaedia (2022). Middle Ages. Britannica Encyclopedia. https://www.britannica.com